Rudenberg v. Delaware DOJ

- Filed: 02/26/2016

- Status: Decided

- Court: Superior Court

- Latest Update: Jun 09, 2017

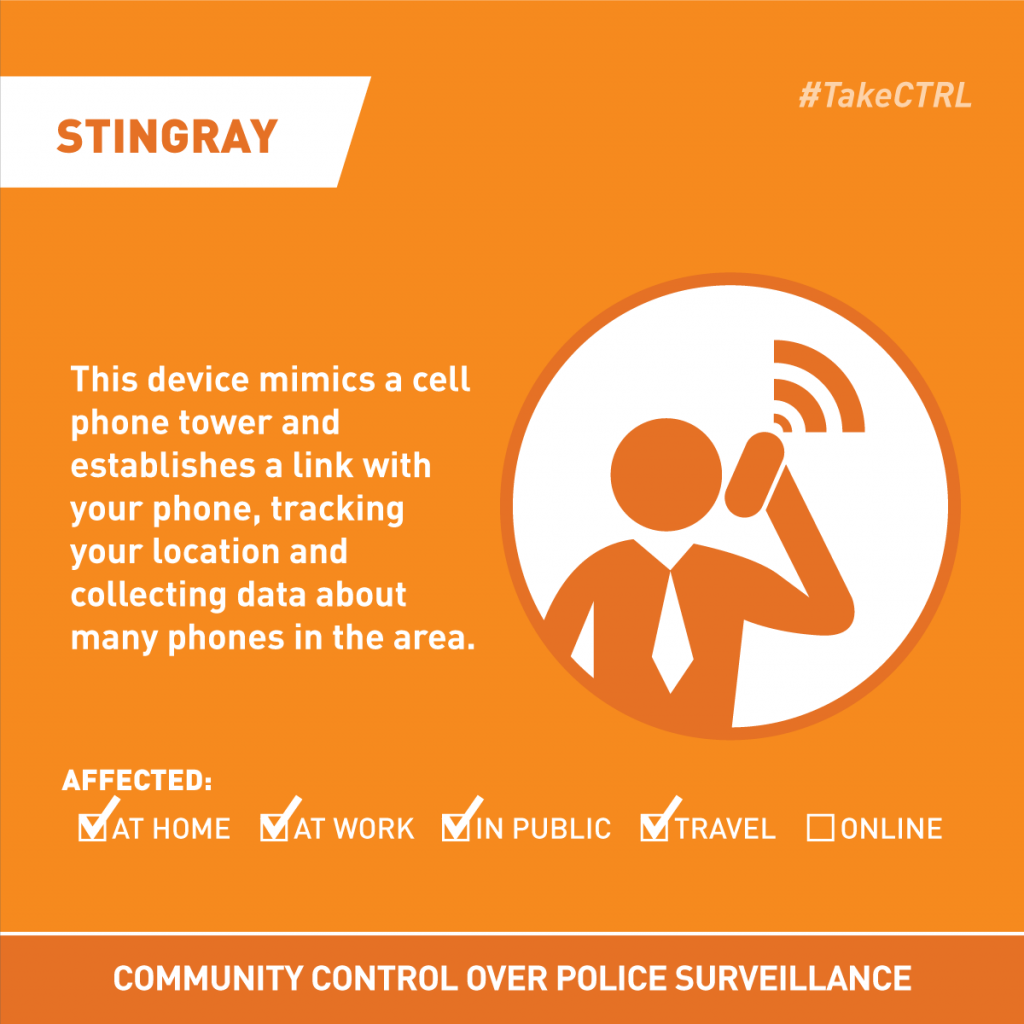

In late 2015, we learned through our client Jonathan Rudenberg's Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request that the Delaware State Police had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase devices that spy on cell phones. DSP didn't want to tell us about that technology. So we sued.

New Police Spying Documents Obtained in FOIA Lawsuit

- 02/26/2016 Harris Corp. NDA

- 02/26/2016 Warrant application example 1

- 02/26/2016 Warrant application example 2

- 02/26/2016 Warrant application example 3

- 02/26/2016 FBI NDA

- 02/26/2016 Notice of Appeal

- 02/26/2016 ACLU Opening Brief

- 02/26/2016 Exhibits.pdf

- 02/26/2016 Compendium

- 02/26/2016 DSP Answering Brief.pdf

- 02/26/2016 ACLU Reply Brief

- 02/26/2016 ACLU Supplemental Brief

- 02/26/2016 DSP Supplemental Brief

- 02/26/2016 ACLU Supplemental Reply Brief

Date Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentDate Filed: 02/26/2016

Court: Superior Court

Affiliate: DE

Download documentLearn More About the Issues in This Case

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.