May 17, 2014 marked the 60th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Delaware was included in the Brown decision. It was one of the states, mostly from the deep South, that mandated racial segregation in its public schools, i.e., de jure segregation. In the infamous decision, Plessy vs. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld de jure segregation if the separate facilities were “equal”.

How Did We Get Here?

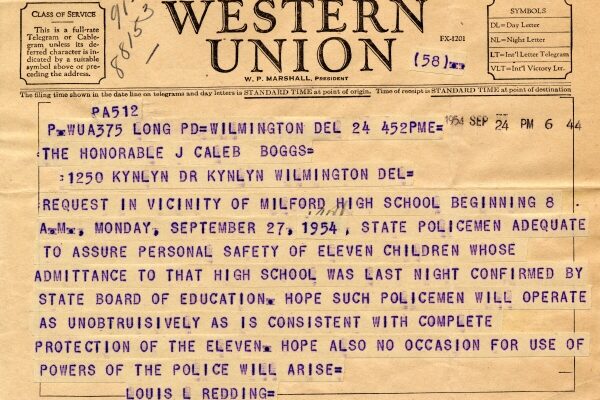

A telegram from Louis Redding to Gov. J. Caleb Boggs requesting police presence to ensure the safety of 11 African American students starting their first day in the newly desegregated Milford High.

The 1954 Brown decision declared de jure segregation unconstitutional. In the second Brown decision, in 1955, which focused on the remedy for de jure segregation, the Supreme Court ordered the affected states to desegregate their public schools “with all deliberate speed”. Delaware, like many other states, focused on the deliberate more than the speed part of the order.

In 1971, black parents in Wilmington, joined later by the Wilmington School Board, renewed a law suit filed in the mid-1950s to implement the promise of Brown, arguing that the Wilmington schools had never been desegregated despite Brown and Court rulings. After years of contentious litigation, the Wilmington plaintiffs prevailed against the suburban New Castle County school districts and the State of Delaware. The Courts ruled that the City schools were indeed segregated as a result of State action.

A single northern New Castle County school district was formed and the District Court ordered busing across city-suburban lines. In 1981, the single district was divided into the four northern New Castle County districts that exist today. By the end of the 1980s, Delaware was considered a national model for desegregated schools, and, later, Delaware was cited as one of the two states having the most desegregated public schools in the nation.

In 1995, after a series of Supreme Court decisions weakening the requirements for districts to be declared “unitary” and thus no longer required to implement components of a school desegregation remedy, the four districts and State convinced the Court to declare the districts unitary. With the passage of the Neighborhood Schools Act in April 2000, the districts had to assign students to the nearest neighborhood school or justify a deviation from this requirement based on hardship. Critics of the law vigorously argued that segregated schools would be the inevitable consequence. Experience shows the critics were right.

Not a Model Anymore

In 2014, 60 years after the first Brown decision, many things have changed in northern New Castle County’s public schools, but school segregation has returned to Wilmington. As backdrop, the demographics of the public schools have changed. The white percentage across all public schools, including charters, is 43.4% in the county while the African American percentage is 35%, Latino/Hispanic 15%, and Asian 4.6%. White students are a bare majority in Brandywine and about 45% in Red Clay and only about one-third of the students in Colonial and Christina.

Outside of Wilmington, more integrated housing patterns and continued busing of middle and high school students into suburban schools has supported desegregation. African-American superintendents, principals, and teachers are found in suburban as well as city schools.

However, the city’s schools—both charters and traditional schools—especially at the elementary level, have become segregated again, with overwhelming majorities of minority and low-income children. For example, Christina’s four city elementary schools have 63 white students among almost 1500 students. In the four inner city charters, only 7 white students were counted in the 2012-13 school year out of over 1500 students.

The causes of school segregation are complex. Housing segregation, more based on economics than race, plays a role, keeping many minorities in the city. Charters and choice have given both blacks and whites options that have increased segregation. Moreover, many people and organizations are concerned that limits on who can attend certain charter schools affect individual choice and accelerates segregation by race and class.

The Beginning of Our Challenge

Should we care that school segregation has returned, at least in Wilmington, especially if some of this is by individual choice rather than by overtly racist laws? We believe we should. Success in our society increasingly will be for those who can participate in a multicultural environment. Research has shown that teachers prefer to work in schools that are not segregated by race, economic status, or limited in student academic achievement. No, an African American student does not need to sit next to a white student to learn, but desegregated schools by race and class tend to ensure higher academic success for all students in attendance.

Many have now recognized that the United States will need all its citizens to succeed in school to remain a prosperous democracy in the decades ahead. Most significantly, Brown was as much about ending America’s Jim Crow—a system which stigmatized and demeaned one race—as it was about improving educational opportunity for African Americans. The Brown decision was not the end, but the beginning, of our challenge.

____________

Jeff Raffel, Helen Foss and Joseph Rosenthal were all involved in the desegregation effort in New Castle County dating back to the early 1970s. They are also current or former board members of the American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware, which continues to work to fulfill the promise of Brown.